Literature of atrocity is never wholly factual nor wholly invented.:"literature has taken as its task making such

reality possible for the imagination"(Langer).

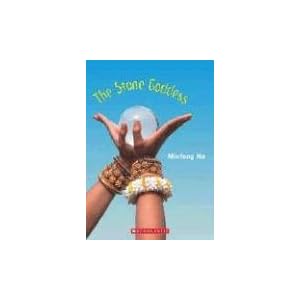

The Stone Goddesss by Mingfong Ho is a first person novel about a middle class urban family in Phnom Penh forced into rural villages and rice fields of Cambodia to work as peasant labor by Pol Pot's Khmer Rough as part of his communist dream of an agrarian society "free" from all evidence of modernity. Nevertheless, the state's attempt to centralize the main commodity, rice, is evidence of the centralizing force in modernity with values nationalism. The novel represents twelve-year-old Nakri's points of view during the relocation, labor in the rice fields, journey to the Thai refugee camp, and "assimilation" into American society after losing her father and sister to the genocide of anyone who did not fit in or follow the profile of Pol Pot's imagined society.

Auhorial strategies of note for this genre of atrocities:

- "personalization": first person narrative, girl, twelve-year-old Nakri; innocent child from an upper class family hiding evidence of modernity to survive the re-education of citizenry

- "parallel experience": siblings with parallel experiences offer different coping strategies to the narrator (Boran, Teeda, Yann)

- "filtering" (come up with a better word for this) by an older sister during possibly "overwhelming" moments; mother also filters towards the end to help the child narrator make sense of her experiences

- "graphic material": Ho resists using confrontational graphic material to simply provoke student interest. Her treatment of the violence in dehumanization in the fields does not seem to distort history. But does it grapple directly with the evil of the Khmer Rouge (Baer)?

- "prose": poetic, narratorial voice is Ho's authorial strategy for negotiating the aesthetic problem of reconciling normalcy and horror

- "imaginative truth": arts focused --aspara dance --cultural and musical tropes as metaphors for turmoil and survival. Does Ho resist constructing an unambiguous hopeful lesson? Is there space for questions (Baer)?

- "instruction in historical fact": Ho does provide proper context of complexity in labor camps, refugee camps, and transition to living in America exploring human agency, but Ho does not craft the story behind the guards who are working in the camps or the other agents....Is there a warning about racism and complacency? The Cambodian genocide is an autogenocide, and so it is different than genocides that have a clear "us" and "them" based on ethnicity or religion. The complacency here is in the international response, but that is not addressed in this novel.

- What is the artist's job? to instruct? to make meaning? to create a framework for response? Is the goal, according to Sullivan, to teach the student about himself, about the hate that is within him, within us all? Is fiction a witness to memory?